How do you choose which form to use? The first step is to read widely and become familiar with lots of different poetic forms. Free verse: A poem written in lines that don’t rhyme but closely follow the natural rhythm of speech.Blank verse: A type of poem that doesn’t have a formal rhyming scheme but is written in a consistent metre (usually iambic pentameter).They usually use an ABCB rhyme scheme and are often quite lengthy! Ballads: Poems that follow rhymed quatrains.These poems usually don’t have a formal rhyming structure. Sestina: A complex form that’s written in six stanzas, each six lines long, with a three-line envoi (a short concluding stanza).

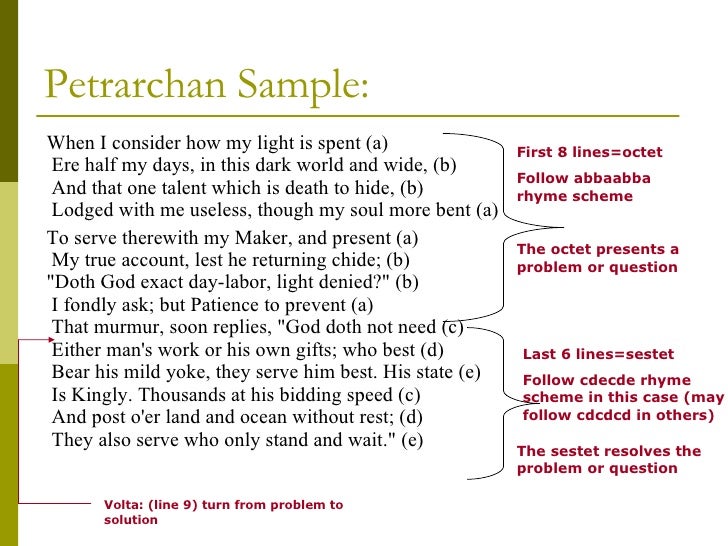

It contains just 17 syllables: five in the first line, seven in the second and five in the third. The haiku: A three-line Japanese poem that’s also highly structured.It’s highly structured, using two repeating rhymes throughout. The villanelle: A 19-line poem, made up of five three-line stanzas and one four-line stanza.Two of the most famous types of sonnet are the Shakespearean (or English) sonnet and the Petrarchan sonnet. This rhyme scheme is dependent on the type of sonnet. The sonnet: A 14-line poem, which usually follows a strict rhyming scheme.

Some of the most common poetic forms include: Some poetic forms are very strict, and the poet should stick to particular rhyming structures when using this form, while others are looser and more open to interpretation.

Poems come in all shapes and sizes, and their form describes the poem’s overarching structure. But it does provide the structure within which your poem, and therefore your choice of poetic devices, sit – and so it’s important to have a good understanding of the different forms you can choose from when you write a poem. Form isn’t exactly a poetry literary technique.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)